Forbidden Worship in Goðdalur

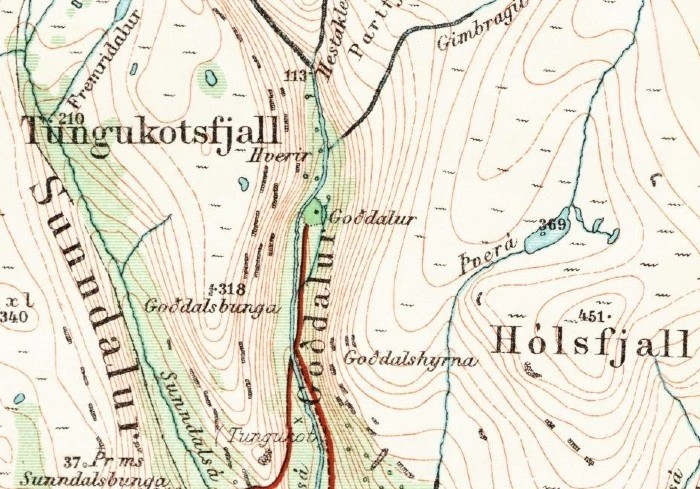

As can be seen on a map of Iceland, Goðdalur in Bjarnarfjörður is extremely remote. It is in the Westfjords, a part of the country many tourists skip entirely on their ring road tour, and it lies in a secluded area of that region. Only a single rough track leads there, a road that is impassable in winter to all but the largest vehicles.

Since ancient times, this larger area has had a reputation for sorcery, with many tales of warlocks and witches. The epicenter and main focus of the Icelandic witch hunts were in the valley’s immediate vicinity. Of those burned at the stake in the 17th century, a strangely high proportion were men from the Strandasýsla county. But the connection to ancient practices goes back even further.

Besides being remote, it was a hard place to live in, especially in winter. Sources tell of two avalanches that destroyed farm homes in the valley, and the latter of these in 1948, left the farm deserted. Six residents died in that event. The farmer and one daughter survived, but she passed away shortly after, and he never fully recovered. Jón Hjaltason wrote about this in Árbók Ferðafélags Íslands 1952 (Yearbook of the Icelandic Travel Association):

“But Goðdalur has previously been the scene of tragic events and accidents. It is as if the anger of the gods (goðagremi) lingers in the valley, and the spirits of the land wish to inhabit it alone.”

Some scholars believe that the old pagan faith survived in the valley for centuries after the adoption of Christianity, and oral traditions tell of a hof, or temple, that once stood there. When Christianity was legalized at the Althing parliament in the year 1000, it was still permitted to worship the old gods in secret. However, if this was discovered and someone was willing to testify, the punishment was three years of exile, and the person could be killed on sight if they did not leave the country for that time. It was not long before this compromise was abolished, and paganism was made entirely illegal.

The valley is named after Goði, its first known settler. He is described as a strongman who did not get along well with his contemporaries. He raided in many lands and became wealthy before settling in this valley. When he felt his death approaching, he gathered all his riches into a large chest, which he is said to have sunk beneath a waterfall in the Goðadalsá river, now called Goðafoss, and ensured that no one would ever be able to find the treasure. He is then said to have been laid to rest in his ship in Goðdalur.

The temple in Goðdalur stood on a hill in the upper part of the valley. After paganism was completely outlawed in the country, it was torn down, and the idols of the gods were taken from their pedestals and thrown into Goðafoss. Still, a sanctity remained on the site where the temple had stood. Nothing was to be disturbed there, lest evil befall. The lush grass on the hill was never cut, and if livestock strayed onto it to graze, it was as if they were driven away by an unseen hand.

Later, a new farm was built on the hill. One of the sources, Ingibjörg Sigvaldadóttir, recalls hearing her father accuse the then farmer in Goðdalur of having disturbed the sanctity of the ruins. The farmer denied it, claiming he had only covered them with a layer of soil and then built the new farm on top. It was upon that farmhouse that the 1948 avalanche fell, leaving the farm deserted.

A little over a decade later, the farmland had been acquired by the couple Inga Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir and Gunnlaugur Pálsson, who built a summer house there between 1960 and 1962. A foundation was dug with an excavator, and they made a habit of setting aside any unusual or interesting stones they found.

One of the stones that drew their attention in particular, is shaped like a three-sided pyramid, with each side measuring about eighteen centimeters. With the wider end turned up, a bowl-shaped cavity can be seen, about five centimeters deep and twenty centimeters wide. It is clearly man-made, as its surface is much smoother than the rest of the stone. Inside the bowl, dark remnants of something can be discerned. This stone was set aside and forgotten for many years.

In the year 2002, the couple came across the stone again and contacted Jón Jónsson, a folklorist in Hólmavík. In consultation with him and the directors of the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft, the stone was sent to forensic specialists at the Reykjavík police department. The stone was sprayed with the chemical Luminol, and further tests were conducted, which revealed that the bowl contained traces of animal blood that were not found anywhere else on the stone.

This result strengthened the suspicion that this was a sacrificial cup, or hlautbolli, used in pagan rituals where animals were sacrificed. It was not possible to date the blood, so one cannot say for certain whether the bowl was used before or after the adoption of Christianity.

The stone’s size, however, could be a clue that it was used for illegal sacrifices. Sacrificial stones used before Christianity could be very large, sometimes being stationary boulders in nature, but this stone weighs only five kilograms, making it easy to hide and transport.

For those who wish to follow ancient paths, Goðdalur in the Strandir region is a unique place. The valley, with its mystique and tangible connection to the pagan faith, could well be considered a worthy destination for modern pagans and followers of Ásatrú. It is important, however, to show respect for the site and its history and to remember that the land is privately owned; therefore, it is essential to ask the landowners for permission before a visit or ceremony. It should also be emphasized that animal sacrifices are a thing of the past, and the slaughter of animals is subject to strict laws and regulations.

For those who are curious but less inclined to make a pilgrimage into a remote valley, the sacrificial stone itself can be seen at the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft in Hólmavík, where it is on display along with a number of other mysterious artifacts.

Sources in English

- The Blood Cup. Museum of Sorcery & Witchcraft

- Valley of the Gods in Iceland. The Norse Mythology Blog