The Brothers from Reynistaður

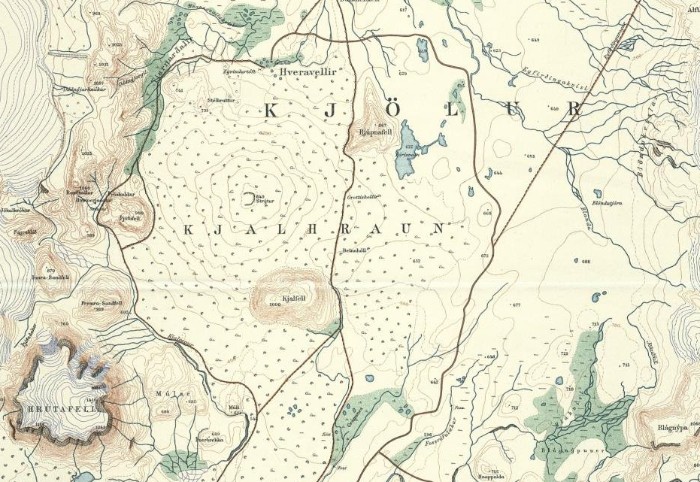

On Saturday, October 28, 1780, two young farmers’ sons, along with three farmhands, set off into the highlands with a group of two hundred sheep and sixteen horses. Their intention was to drive the herd from the South of Iceland, across Kjölur, the area between Langjökull and Hofsjökull glaciers, north to Reynistaðir farm in Skagafjörður. Many warned them against attempting this route at that time of year, but they declined offers of winter lodging. The next day, a violent snowstorm struck that lasted for several days.

The sheep they were driving were meant to restore their parents’ flock, which had all been slaughtered due to sheep scab. The brothers were from a distinguished family on both sides. Their father, Halldór, held authority over and managed the lands of Reynistaðarklaustur convent on behalf of the king and had been born into wealth, but due to the sheep scab and years of poor harvests, that wealth had greatly diminished.

The older brother, Bjarni Halldórsson Vídalín, who was eighteen or nineteen according to most sources, though some claim he was only fourteen, had been sent in midsummer along with the overseer Jón Austmann, carrying silver and banknotes to buy uninfected sheep in the southern and eastern parts of the country. Einar, who was eleven years old, was sent later with a farmhand to help drive the flock north. Einar had pleaded desperately with his mother, Ragnheiður, not to be sent, but when she remained firm in her decision, he gathered his playmates to say goodbye and divide his toys among them.

It has been suggested that the reason he was sent at such a young age was in the hope that his father’s friends would be more likely to give him sheep or be more willing to sell, as there was high demand for uninfected livestock due to the outbreak of sheep scab.

They had been forced to travel far to purchase the sheep and had to wait until after the round-up to receive much of it. Therefore, their return journey was delayed. Bjarni, who was a student at the Hólar School, had inquired whether he might spend the winter at the Skálholt School so that his graduation would not be delayed, but ended up in a dispute with the schoolmaster, perhaps because the schoolmaster was unwilling to recognize the studies at Hólar as equivalent to those at Skálholt. This was likely one reason why Bjarni was determined to head north despite warnings. It may also be that he wished to spare the family the cost of winter feeding. Jón Austmann, who also had authority in the matter and was described as a harsh and unyielding man, may likewise have had his own reasons for not wishing to linger in the south. So off they went, and a teenage boy joined the group, having been hired for the journey with the possibility of further work in the north.

There was little to no communication between regions during the winter, and no news arrived as to whether or when the expedition had set out. They had been expected back in the autumn, but as the winter wore on, the people at Reynistaðir grew increasingly anxious.

At the tenant Jón’s farm at Hryggir, ghostly activity began to take place, and he believed that Jón Austmann had come there, with whom he had been in bitter dispute. His wife also became aware of Austmann, who had been responsible for collecting rent from the leaseholds overseen by Halldór Vídalín and was considered to be harsh in his dealings.

Jón at Hryggir was reputed to have second sight, and the boys’ mother asked him what he thought had become of the expedition when they met at church. He replied that he believed Jón Austmann was with the devil, but as for the others, he did not know. On that same church visit, he thought he saw the brothers huddled together in one of the church’s rooms and took it as certain that they were dead, but said nothing of it to their mother.

Their sister Björg had a dream in which a verse came to her that she remembered upon waking, and it later became known across the country:

No one may find us here

beneath the crust of snow.

Three days by the body

Bjarni sat in sorrow.

The weather did not allow for sending out search parties until shortly before Christmas, when it became calm and the ground was hard with frost. Then two men rode south and received news that the expedition had set off north long ago. They hurried back and saw no sign of the group except for about twenty sheep, which they drove closer to settled areas. Then the weather worsened again and prevented any further search.

It was later reported that during the winter, men searching for stray sheep heard strange sounds or calls while traveling across Kjölur, but had not investigated further, possibly out of fear of ghosts or outlaws.

A few sheep from the flock came down to settled areas that winter, as did the sheepdog. Early in the spring, when horses were being gathered into the fold to be clipped after the winter, a stallion from the expedition came neighing to the pen. Halldór, the brothers’ father, witnessed this and was so affected that he took to his bed for a week.

Finally, a farmer found the expedition’s tent in Kjalhraun lava field. He believed there were four bodies in it, though others who were with him said there were three. Jón Austmann was not among them. There was a strong smell of death in the tent, so he and his companions did not examine it further but piled stones on the edges of the tent and marked the spot.

The farmer Tómas from Flugumýri went to Reynistaðir to report the discovery, and a group was sent out to retrieve the bodies and bring them back to the farm. Tómas went along to show the way. But when they returned, the brothers’ bodies were no longer there.

There was nothing of value in the tent, but as later came to light, the older brother, Bjarni, had been carrying a purse with the money that had not been used to purchase sheep. From the signs at the site, it appeared that the tent-dwellers had survived for a time on raw mutton, as a number of bones lay beside the tent. It was believed that they had been forced to stop there, and that Jón Austmann had attempted to seek help.

Jón Austmann’s horse was later found dead in a branch of the Blanda river, and it was believed that the horse had fallen there and Jón had been unable to get it back out. A saddle and riding gear lay nearby on a mound, and the horse had been cut at the throat, and its head tucked beneath one shoulder. Some years later, a human hand was found at another spot by the river, in a mitten bearing Jón’s initials, and in 2010, a fragment of a human skull was discovered in the same area.

Halldór wrote to many of his neighbors and asked them to help him search for the brothers, and many from Skagafjörður went south onto Kjölur to take part, but none were any the wiser. Around the same time, Jón at Hryggir dreamed that little Einar came to him and recited this verse:

In a rocky crevice, crouched are we two,

But once in a tent,

all were comrades true.

The parents of the brothers were deeply grieved that their bodies had not been found, and they organized many search expeditions in the following years, sparing no expense. They also kept up inquiries about people’s movements across Kjölur around the time the tent was discovered, and learned that three men had passed close by the site during that period. One of them had taken part in the search early that spring. Suspicion fell on the three that they had robbed the brothers’ bodies without knowing the tent had already been found, and then hidden them to make it appear as if the brothers had vanished with the money in their possession.

A case was brought against them, with many assemblies and trials held, numerous witnesses called, and even a man skilled in magic enlisted to try to find the brothers and extract a confession by sorcery, but nothing proved effective. They were acquitted, as their guilt was not considered proven, and were granted the right of denial oath — that is, they could swear that they were innocent.

The brothers’ parents were not satisfied with the verdict and appealed the case to the Alþingi. The matter dragged on, but five years later the district court’s verdict was upheld by the governor. One of the accused had by then died, but the remaining two never swore the oath for unknown reasons. They in turn filed a complaint and demanded compensation from Halldór Vídalín for the accusation and the troubles it had caused, but that case was dismissed.

Nearly seventy years and two generations later, news came from Kjölur to the brothers’ niece, who was then living at Reynistaðir, that human bones had been found. They were some distance from the tent site, beneath stones and slabs of rock, and at first it seemed unlikely that they belonged to the brothers, so they were not retrieved until five years later. A doctor examined them and believed they were from individuals of the same age as the brothers, though that conclusion has later been questioned by some. The bones were nonetheless eventually buried under the brothers’ names.

The fate of the Reynistaðir brothers had such a profound impact that, after this, travel along the Kjölur route nearly ceased for more than a hundred years, though it had previously been the main route between the South and North of Iceland. The event remained with the Reynistaður family and appeared, among other things, in the superstition that men of the lineage must not wear green clothing or ride a pale horse, as the older brother had done, although according to testimony in the court records, he was in fact not wearing any green garments. It was also believed and written that depression followed the family, said to have its roots in the sorrow and guilt the brothers’ parents felt for sending them on the journey, especially the younger.

Few criminal cases in Iceland have been written about as extensively, for corpse theft is particularly disturbing and rare. Many theories have been proposed based on various assumptions. For example, that there were never more than two bodies in the tent, that they were under bedcovers, and those who found the tent either could not or would not examine it more closely. Or that someone had hidden the brothers’ bodies to torment the parents. Or that Jón Austmann had killed the brothers, fled with the valuables and part of the sheep, and intended to take up with outlaws.

There have been reports of strange shadows on Kjölur, which may perhaps be connected to the expedition. These shadows fall upon tents and are visible to all those inside, clearly bearing the shape of human figures. But when one steps outside the tent, no one is there.

Sources in English

- The Kjolur Route. Ancient Origins

- Lingering Shadows (audiobook) (2012). Bjarni Skúli Ketilsson

- Reynistaður brothers are home, 238 years after leaving. Iceland Monitor

Sources in Icelandic

- Afdrif Jóns Austmanns, fyrri hluti. Tíminn Sunnudagsblað, 25. september 1966

- Afdrif Jóns Austmanns, seinni hluti. Tíminn Sunnudagsblað, 2. október 1966

- Gullkorn Jónatans Hermannssonar, Reynistaðarmenn. Litli Bergþór, 1. júní 2022

- Hvað gerðist á Kili 1780? Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 19. október 1969

- Hver fjarlægði lík Staðarbræðra? Skírnir, vor 2012

- Leyndarmál öræfanna. Fornir skuggar (1955). Tómas Guðmundsson

- Reynistaðarbræður. Hrakningar og heiðavegir, 1. bindi (1950). Pálmi Hannesson, Jón Eyþórsson

- Reynistaðarbræður. Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 11. janúar 1970

- Staðarbræður. Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 23. nóvember 1969

- Skuggarnir á Kili. Gráskinna hin meiri, 1. bindi (1962). Sigurður Nordal, Þórbergur Þórðarson