Strandarkirkja Church

On a windswept plain by the open sea stands a small, unassuming country church. It doesn’t look like much, yet it is the most famous church in Iceland. It is also the richest, due to pledges made to it over a long time. The pledges are only fulfilled if what is prayed for comes true. Therefore, its wealth is the main proof of its power.

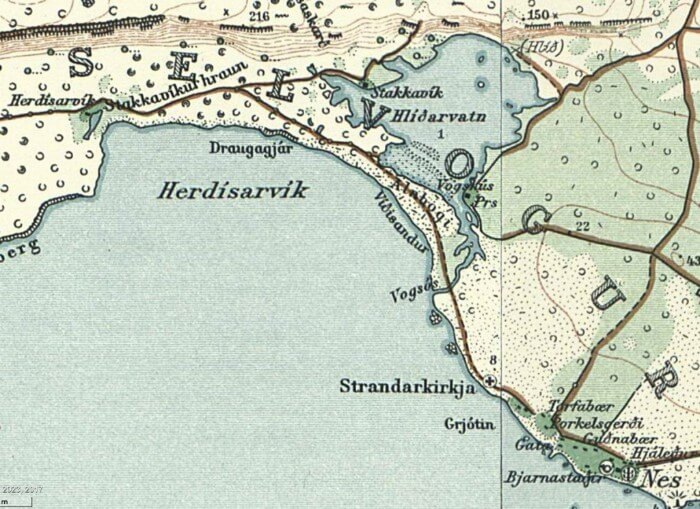

A sacred legend about the first church built there has been passed down through generations in Selvogur. Early in the Middle Ages, possibly shortly after the Christianization, a ship sailed between Norway and Iceland carrying wood for construction. The ship ran into peril near Selvogur coast, and the crew vowed to build a church from the timber if they survived. Then, a glowing being appeared to them on the shore, some say before the prow, guiding them to a safe landing near what is now called Engilsvík. They kept their pledge and built the church, which was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and Thomas of Canterbury.

Pledges have been made to this church for nearly a thousand years for matters of varying seriousness. These range from illness and life-threatening situations, to prayers for finding love, to not being late. The pledges are almost always prayers for good, but at least one of them was about making things difficult for someone else.

Writer Þórbergur Þórðarson recorded the account of a man who intended to travel with friends to Þingvellir from Reykjavík, but they set off without him. Angered, the man made a pledge of donating to Strandarkirkja if they would not make it all the way; at that time, it was three o’clock. In the evening, he heard from one of the group who had set off for Þingvellir and learned that when the group, traveling in a horse-drawn cart, was on Mosfellsheiði around three o’clock, the horses suddenly stopped and refused to go further. No matter how they tried, pulling them, whipping, unharnessing and mounting, nothing worked. After a few hours, they gave up and turned back. Then the horses ran back to Reykjavík in a single sprint.

Years later, Þórbergur recorded the account of a woman who was traveling in the opposite direction on the same day at the same time. She saw the cart and the men struggling to get the horses to move, who stood still as if made from stone.

The church is first mentioned in records from the 13th century. During Catholic times, it was common to make pledges to saints and churches, and there are no specific accounts of pledges made to the church from that time. However, it seems to have received unusually many donations, as these were counted as sources of income, which was not the norm.

The church currently standing was originally built in 1888, with the nave remaining original. It was renovated and reconsecrated in 1968. Many church buildings have stood there, often endangered by natural forces that laid the land around it to waste, leaving it isolated. Sometimes it was threatened by church authorities who tried three times to relocate it. Due to opposition from parishioners, support from allies within and outside the National Church, and possibly by its own power, it still stands on the same site.

The first attempt to relocate the church involved a priest, provost, bishop, and governor who granted its relocation. In 1751, the bishop ordered the church to be torn down and a new church built at Vogsósar, where the priests usually resided. He gave two years for the demolishing to start, but before that time elapsed, the provost and bishop had died, the priest had moved or fled, and the governor had been dismissed. Attempts were made again in 1756 and 1820, but due to opposition from parishioners and the parish priest, they were unsuccessful.

For centuries, Strandarkirkja was located on the estate of Strönd, one of the main homesteads of the Erlendingar clan and where they lived for eight generations. The clan is named after Erlendur, nicknamed “the Strong,” Ólafsson, a knight and lawman about whom folklore exists. He was born around 1235, and the ruins of the homestead can still be seen north of the church.

At that time, the area was fertile, with several smaller farms apart from the main homestead. A forest grew there, a bird cliff where eggs were harvested is nearby, as well as rich fishing grounds, and driftwood was plentiful. According to folklore, the first signs of land degradation appeared in the 16th century. It is said that Erlendur Þorvaldsson, a descendant of Erlendur the Strong and known for being ill-tempered when drinking, killed his shepherd for bringing news that he had found sand on the land. Erlendur declared he would not have a man in his service who brought him such bad news. The homestead was abandoned in 1696, and all settlement near the church was wiped out by 1762.

Strandarkirkja has had many priests over the centuries. In the final years of the Erlendingar on the site, the priest was Reverend Eiríkur Magnússon (1638–1716) from Vogsósar. He is one of the better-known sorcerers in Icelandic folklore, and many stories were told about him. He is buried in a now-lost grave in the churchyard or, according to a former sexton, in front of the altar.

The tradition of pledges as known today and the increased popularity of making these to Strandarkirkja goes back to the 18th century. Bjarni Sívertsen, known as the father of Hafnarfjörður, grew up in Selvogur near the church. In 1778, at age 14 or 15, he pledged to the church, asking that he would amount to something in life. Sixteen years later, he fulfilled that vow by donating a pulpit to the church.

No special rituals are required to pledge donations to Strandarkirkja. It is enough to pray: “I pledge to Strandarkirkja that if … then …” Today, money is most often donated, but in earlier times, objects and possibly services were more common. The amount does not matter as much as the intention, and gifts have typically been small. Occasionally, though, large sums have been received. Witnesses are not required for the pledge, and it does not need to occur at or near the church. Nothing needs to be given beforehand—only after the pledge is answered. There are no stories about what happens if a pledge is not fulfilled.

In the late 19th century, newspapers began publishing amounts of pledges to various places, effectively advertising Strandarkirkja. Some church officials disapproved of this superstition. In 1892, the editor of Kirkjublaðið, later the bishop of Iceland, wrote against pledges to Strandarkirkja, stating that many priests shared his view.

The article expressed outrage and described the practice as either a remnant of Catholicism, a mercenary bargain with God, or an appeal to the magical powers of Reverend Eiríkur at Vogsósar. It argued there were many needy churches in the country and that Strandarkirkja, being so wealthy, should not monopolize such donations.

These writings reveal the attitude of church authorities at the time and possibly later. They found the practice inconvenient, as it did not fit Protestant doctrine, and there is a hint of jealousy toward the church. Yet it was Strandarkirkja’s wealth that funded the maintenance of other churches. In the 19th century the General Church Fund was established, financed mainly by donations to Strandarkirkja, which continues lending to other churches for maintenance to this day.

At times the church itself received nothing and lacked necessary maintenance. It seems church authorities tried to rid themselves of this misfit by letting nature destroy it. When a bill was proposed in Parliament in 1928 to use part of the donations to combat soil erosion near the church, it faced opposition from church representatives, including the bishop. However, the bill passed, and today the results of revegetation efforts can be seen. Where there were once only drifting black sands and bare lava, hardy vegetation now grows.

Today, church authorities are much more supportive of Strandarkirkja. Both priests and bishops have spoken highly of it in sermons and writings. The church is well maintained, and measures have been taken to accommodate the increasing interest of visitors.

If anyone faces a challenge, whether serious or not, or simply wants to test the church’s power by praying and pledging for something, it is easy to do. On the church’s website, there is a tab for making donations with a credit card, located at the top right. Tradition holds that the pledge does not need to be fulfilled unless the prayer is answered, and then this tab can be used.

Sources in English

- A Shrine by the Sea. American-Scandinavian Review, no. 4 1958

- Strandarkirkja (1990). Rev. Magnús Guðjónsson

- Strandarkirkja. Wikipedia

Sources in Icelandic

- Á eyðilegum stað við úthafið. Ægir, nóvember 2007

- Áheitin á Strandarkirkju. Kirkjublaðið, júlí 1892

- Áheitin á Strandarkirkju. Helgarpósturinn, 16. febrúar 1984

- Eitt af kraftaverkum Strandarkirkju. Nýja dagblaðið, 19. júní 1934

- Engilsvík. Kirkjuritið, 1953

- Erindi um Strandarkirkju. Lesbók Morgunblaðsins, 2. október 1927

- Friðaðar kirkjur í Árnesprófastsdæmi (2003). Margrét Hallgrímsdóttir et al.

- Gráskinna hin meiri (1962). Sigurður Nordal og Þórbergur Þórðarson

- Heimsókn á helgan stað. Eimreiðin, júlí–desember 1948

- Í sjónmáli fyrir sunnan (1980). Jón R. Hjálmarsson

- Strandarkirkja í Selvogi (1991). Sr. Magnús Guðjónsson

- Strandarkirkja, helgistaður við haf (1993). Jón Hnefill Aðalsteinsson

- Strandarkirkja. Strandarkirkja.is

- Þjóð í Önn (1965). Guðmund Daníelsson

- Þjóðsögur við þjóðveginn (2000). Jón R. Hjálmarsson