The Outlaws of Þórisdalur

Outlaws occupy a distinct category in Icelandic folklore and were originally exiles who had fled into the wilderness, either with their family or they abducted women from settlements. Their descendants were known as mountain dwellers and lived in seclusion in the wilderness for generations, going back to the time of the Icelandic Sagas.

The highlands were long unexplored, and it was believed that outlaw settlements existed in mountain valleys that few could find and were sometimes hidden by magic. There was interaction between the outlaws, and they formed a small nation that kept to itself and maintained joint defenses against encroachment from the other nation. It happened that shepherds got lost on the highlands and fell into their clutches, they would not live to tell the tale unless the mountain dwellers spared their lives in exchange for a promise of secrecy and some favor.

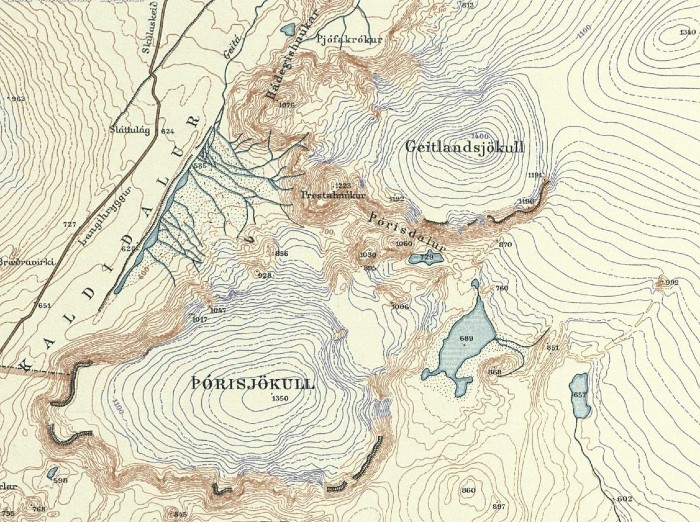

In or near Geitlandsjökull glacier, located in the western end of Langjökull glacier, there was said to be an outlaw settlement in Þórisdalur valley. Due to similarities with other accounts of hidden outlaw valleys, it is believed to be the same valley as Valadalur and Áradalur. What is known today as Þórisdalur is mapped between the glaciers Geitlandsjökull and Þórisjökull.

The oldest source that mentions the valley is Grettir’s Saga. It is one of the places where Grettir seeks refuge during his outlaw years. He finds his way there using directions from Hallmundur, who had sheltered him in his cave near Langjökull glacier. Grettir discovers the valley by ascending the northern part of Geitlandsjökull and crossing it southward until he arrives at a long, narrow valley surrounded by overhanging glacier ice. There, he finds grassy slopes, shrubbery, and hot springs, which he believes keep the glacier from closing, but little sunlight reaches it. A small river runs through it, and Grettir is surprised by how fat the sheep are there.

The ruler of the valley is named Þórir, and Grettir names it after him. It is by his permission that Grettir stays there. Þórir is a hybrid, half-man and half-rock giant. But some of the settlers who came to Iceland about a hundred years earlier were also of that lineage, including Egill Skallagrímsson. No other residents of the valley are mentioned besides Þórir’s daughters, with whom Grettir forms a friendship. Grettir stays through the winter until he grows tired of the isolation. He then travels south out of the glacier and up the mountain Skjaldbreiður, where he erects a stone slab, carves a notch into it, and says that if one looks along it, they can see a gorge with a stream flowing from the valley. A source states that at the beginning of last century, a shepherd found a large stone slab on the northern slope of Skjaldbreiður that was split in the middle along a notch and had visibly been propped up but fallen and broken.

If Þórisdalur is the same as Áradalur, mentioned in the plural in the source that follows, then Þórir was not the first inhabitant, but took over the valley after killing its first discoverer, Skegg-Ávaldi or Skugga-Valdi. Jón lærði Guðmundsson (1574–1658), who had an interest in hidden valleys among many other things, wrote about Skegg-Ávaldi.

In a work by Jón, Ein stutt undirrétting um Íslands aðskiljanlegar náttúrur, that translates A Brief Explanation of Iceland’s Various Natures, it is said that among the first settlers in Iceland were those who had learned “to open and close cliffs, to enter and exit at will, such as Bárður í Jökli, Hámundur í Hámundarhelli, Bergþór í Bláfelli, Ármann í Ármannsfelli, and Skegg-Ávaldi, who discovered Áradalur and became its god, as the people there prayed, ‘Skegg-Ávaldi, watch over your land, so that Áradalur remains unfound.'” These rock dwellers appear in the Icelandic Sagas, and Skegg-Ávaldi is supposedly the same as Ávaldi Ingjaldsson in Vatnsdæla Saga.

In Áradalsóður or Áradalur’s Ode, also composed by Jón lærði, the valley is mentioned in the singular. Several legends told there can also be found in Jón Árnason’s folklore collection. Skegg-Ávaldi is said to have lived in the valley, hidden it with magic, and moved there with his people, who were of pagan faith. By the time Grettir arrives, Iceland has been Christian for over half a century, and at least Þóris daughters were Christian. They observe Lent before Easter, and Grettir tells them it is okay to eat liver and fat during it.

However, according to Áradalsóður, the people remained faithful to the old Norse gods under Skegg-Ávaldi. A man dreams of entering the valley and is told not to mention the Christian god. To prove the dream’s truth, he is given a sheep with a distinct marking, which later appears in the fall roundup.

The connection to Þórir in Þórisdalur comes from a text written in 1780, possibly based on older tales. In Ármanns saga hin yngri, that translates as The Younger Ármann’s Saga, set a hundred years before Grettir’s time, Skugga-Valdi is said to have lived in Valadalur. Due to his name’s similarity to Skegg-Ávaldi, it is thought to refer to the same person. Valadalur is also said to lie east of Skjaldbreiður mountain like Þórisdalur and is surrounded by glaciers. The Saga recounts how Þórir’s father steals sheep from Skugga-Valdi, who kills him in revenge. Þórir then seeks out Skugga-Valdi in his cave in Valadalur and avenges his father with the help of Ármann í Ármannsfelli. He then claims the valley, its sheep, and moves there with his wife and daughters.

In Lítið ágrip um hulin plass og yfirskyggða dali á Íslandi, that is A Brief Account of Hidden Places and Concealed Valleys in Iceland, attributed to either Jón lærði Guðmundsson or Jón Eggertsson á Ökrum, it is written that a man named Teitur led a group of twelve in search of the valley. They were enveloped in thick fog, and Teitur heard a voice coming from it, warning him to turn back or he would be taken by trolls, so they did.

Most of these stories were likely familiar to two clergymen in the 17th century, who decided in 1664 to attempt finding the valley with two companions, about half a millennium after Grettir had visited it. One priest, Helgi Grímsson, had long been interested in Þórisdalur and had earlier tried to mount an expedition. His father, Grímur Jónsson of Húsafell, had been a servant of Bishop Oddur Einarsson and was with him on a journey across Ódáðahraun lavafield, which was known as an outlaw area. They got lost in fog but were helped by outlaws who gave them a horse, provisions, and directions to the Jökulsá river.

The other priest, Helgi’s brother-in-law Björn Stefánsson, also wrote about the journey, though he did so much later. They met in Kaldidalur, a main travel-route over the highland in those days, and decided, as the weather was good, to go search for the valley, intending to convert any outlaws they found.

They brought no weapons, only bread and a bottle of alcohol, assuming the outlaws would appreciate these. A boy with them was meant to be lowered down over a ledge by the valley, if necessary to scout ahead but it didn’t come to that and he was instead left to watch the horses at one location.

After some effort, they reached a place where they could overlook Þórisdalur near Geitlandsjökull but could not descend into it. They concluded there was no thriving outlaw settlement there and returned after exploring a nearby cave, which they thought likely to have been the dwelling og Þórir the half-giant. Their journey made them famous for their bravery in venturing into outlaw territory.

Almost a century passed until the valley was searched for again, as far as records show. In 1753 explorers Eggert and Bjarni attempted to go there but were forced to turn back due to weather. In 1833, teacher Björn Gunnlaugsson climbed Skjaldbreiður mountain with a telescope to study Geitlandsjökull’s glacier edge. He saw the mouth of a valley but could not discern its depth. The following year, he climbed Bláfell mountain in Árnessýsla county and used the telescope to spot a large, unknown valley cutting through Geitlandsjökull, extending from the valley mouth seen the year before. He continued his expedition to Langjökull glacier, eventually finding a clear view of Þórisdalur.

Björn returned in July 1835 to study the valley more thoroughly, this time with six companions. They managed to descend on foot into the valley and confirmed the priests’ account that it had little vegetation and no hot springs. Geothermal activity might however have existed during Grettir’s time, as a nearby volcanic eruption had occurred a relative short time before. In 1895, two Germans tried to explore the valley but were unable to enter. In 1909, an Austrian named Wunder ventured into it and became the first to measure its elevation, which was found to be 500 meters above sea level.

Thus Þórisdalur valley had finally been formally located . But one might ask if this was indeed the famed hidden valley, for it is suspiciously easy to find and close to a well-traveled route. Although earlier explorers struggled to descend into the valley, they could usually reach it when the weather permitted, and today it is not that hard to access by seasoned hikers, as the glacier has retreated significantly.

A valley is marked on today’s maps as Þórisdalur, but isn’t the most effectively way to hide something, to make the searchers believe they have already found it?

Sources in English

- Grettissaga. Icelandic Saga Database

- Grettis saga. Wikipedia

- Langjökull. Wikipedia

- The Legends of the Outlaw. Reykjavik Grapevine

- Stories of Outlaws. Icelandic Legends Collected by Jón Árnason (1866). Jón Árnason

Sources in Icelandic

- Ármanns saga in yngri. Heimskringla

- Ein stutt undirrétting um Íslands aðskiljanlegar náttúrur (1740). Jón Guðmundsson

- Ferð í Þórisdal. Eimreiðin, júlí 1918

- Frásagnir úr Áradalsbragnum. Fróðarsteinn

- Grettissaga. Icelandic Saga Database

- Munnmælasögur 17. aldar (1955). Bjarni Einarsson

- Um Þórisdal. Sunnanpósturinn, ágúst 1836

- Um fund Þórisdals. Skírnir, 1834

- Útilegumannasögur. Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og ævintýri (1954). Jón Árnason

- Útilegumannasögur. Íslenskar þjóðsögur og sagnir (1988). Sigfús Sigfússon

- Útilegumenn í Þórisdal. Landinn, desember 2019

- „Þá brosti allt kompaníið.“ Þjóðviljinn, 28. ágúst 1963

- Þórisdalur og ferð prestanna 1664 (1997). Eysteinn Sigurðsson

- Þórisdalur. Wikipedia